Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution

| United States of America |

This article is part of the series: |

| Original text of the Constitution |

|---|

| Preamble Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

| Bill of Rights I · II · III · IV · V VI · VII · VIII · IX · X Subsequent Amendments |

|

Other countries · Law Portal |

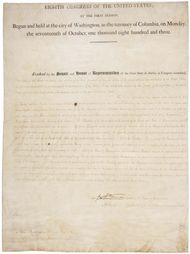

The Twelfth Amendment (Amendment XII) to the United States Constitution provides the procedure by which the President and Vice President are elected. It replaced Article II, Section 1, Clause 3, which provided the original procedure by which the Electoral College functioned. Problems with this procedure were demonstrated in the elections of 1796 and 1800. The Twelfth Amendment was proposed by the Congress on December 9, 1803 and was ratified by the requisite number of state legislatures on June 15, 1804.

Contents |

Text

| “ | The Electors shall meet in their respective states, and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and they shall make distinct lists of all persons voted for as President, and all persons voted for as Vice-President and of the number of votes for each, which lists they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate.

The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted. The person having the greatest Number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President. But in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the states, and a majority of all the states shall be necessary to a choice. And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in the case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.[1] The person having the greatest number of votes as Vice-President, shall be the Vice-President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed, and if no person have a majority, then from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President; a quorum for the purpose shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of Senators, and a majority of the whole number shall be necessary to a choice. But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.[2] |

” |

Electoral College before the Twelfth Amendment

Under the original procedure for the Electoral College, as provided in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3, each elector could cast two votes. Each elector could not vote for two people inhabiting the same state as that elector.[3] If exactly one person received a vote from a majority of the electors, that person won the election.

If there was more than one individual who received a vote from a majority of the electors, the House of Representatives would choose one of them to be President. If no individual had a majority, then the House of Representatives would choose from the five individuals with the greatest number of electoral votes. In either case, a majority of state delegations in the House was necessary for a candidate to be chosen to be President.

Selecting the Vice President was a simpler process. Whichever candidate received the greatest number of votes, except for the one elected President, became Vice President. The Vice President, unlike the President, did not require the votes of a majority of electors. In the event of a tie for second place between multiple candidates, the Senate would choose one of them to be Vice President, with each Senator casting one vote. It was not specified in the Constitution whether the sitting Vice President could cast a tie-breaking vote for Vice President under the original formula.

In the 1796 election, John Adams, the Federalist Party presidential candidate, received a majority of the electoral votes. However, the Federalist electors scattered their second votes, resulting in the Democratic-Republican Party presidential candidate, Thomas Jefferson, receiving the second highest number of electoral votes and thus being elected Vice President.

The 1800 election exposed a defect in the original formula in that if each member of the electoral college followed party tickets, there would be a tie between the two candidates from the most popular ticket. It also showed that the House of Representatives could end up taking multiple ballots before choosing a President.

Additionally, it was becoming increasingly apparent that a situation in which the Vice President had been a defeated electoral opponent of the President would impede the ability of the two to effectively work together, and could provide motivation, at least in theory, for a coup d'état (since the Vice President would succeed to the office of the President upon the removal or death of the President). In having the President and Vice President elected as a ticket, the Twelfth Amendment eliminated this possibility, or at least minimized it by lessening the Vice President's motivation for staging such a coup.

Electoral College under the Twelfth Amendment

The Twelfth Amendment changed the process whereby a President and a Vice President are elected. It did not change the composition of the Electoral College. It has applied to Presidential elections since 1804.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, each elector must cast distinct votes for President and Vice President, instead of two votes for President. Pursuant to the Habitation Clause, no elector may vote for both candidates of a presidential ticket if both candidates inhabit the same state as that elector.

The Twelfth Amendment explicitly precluded those constitutionally ineligible to be President from being Vice President.[4][5]

A majority of electoral votes is still required for one to be elected President or Vice President. When nobody has a majority, the House of Representatives, voting by states and with the same quorum requirements as under the original procedure, chooses a President. The Twelfth Amendment requires the House to choose from the three highest receivers of electoral votes, compared to five under the original procedure.

The Senate chooses the Vice President if no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes. Its choice is limited to those with the "two highest numbers" of electoral votes. If multiple individuals are tied for second place, the Senate may consider all of them, in addition to the individual with the greatest number of votes. The Twelfth Amendment introduced a quorum requirement of two-thirds for the conduct of balloting. Furthermore, the Twelfth Amendment provides that the votes of "a majority of the whole number" of Senators are required to arrive at a choice.

In order to prevent deadlocks from keeping the nation leaderless, the Twelfth Amendment provided that if the House could not choose a President before March 4 (at that time the first day of a Presidential term), the individual elected Vice President would act as President, "as in the case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President." The Twelfth Amendment did not state for how long the Vice President would act as President or if the House could still choose a President after March 4. Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment replaced that provision of the Twelfth Amendment by changing the date for the commencement of Presidential terms to January 20, clarifying that the Vice President-elect would only act as President if the House has not chosen a President by January 20, and permitting the Congress to direct, through legislation, "who shall then act as President" if there is no President-elect or Vice President-elect by January 20. It also clarified that if there is no President-elect on January 20, whoever acts as President does so until a person "qualified" to occupy the Presidency is elected to be President.

Elections since 1804

Starting with the election of 1804, each Presidential election has been conducted under the Twelfth Amendment.

Only once since then has the House of Representatives chosen the President: In 1824, Andrew Jackson received 99 electoral votes, John Quincy Adams (son of John Adams) 84, William H. Crawford 41 and Henry Clay 37. All of the candidates were members of the Democratic-Republican Party (though there were significant political differences among them), and each had fallen short of the 131 votes necessary to win. Because the House could only consider the top three candidates, Clay could not become President. Crawford's poor health following a stroke made his election by the House unlikely. Andrew Jackson expected the House to vote for him, as he had won a plurality of the popular and electoral vote.[6] Instead, the House elected Adams on the first ballot with 13 states, followed by Jackson with seven and Crawford with three. Clay had endorsed Adams for the Presidency; the endorsement carried additional weight because Clay was the Speaker of the House. When Adams later appointed Clay his Secretary of State, many — particularly Jackson and his supporters — accused the pair of making a "Corrupt Bargain".[7] In the less contested election for vice president, John C. Calhoun received 182 votes and was elected outright.

In 1836, the Whig Party nominated different candidates in different regions in the hopes of splintering the electoral vote and denying Martin Van Buren, the Democratic candidate, a majority in the Electoral College, thereby throwing the election into the Whig-controlled House. However, this strategy failed with Van Buren winning majorities of both the popular and electoral vote. In that same election no candidate for Vice President secured a majority in the electoral college as Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Richard Mentor Johnson did not receive the electoral votes of Democratic electors from Virginia, because of his relationship with a former slave. As a result Johnson received 147 electoral votes, one vote short of a majority; to be followed by Francis Granger with 77, John Tyler with 47 and William Smith with 23. This caused the Senate to choose whether Johnson or Granger would be the new Vice President. Johnson won with 33 votes, with Granger receiving 17.

There have been no further attempts by a major U.S. party to adopt the strategy of running multiple regional candidates for national office since 1836. However, since the Civil War there have been two serious attempts by Southern-based parties to run regional candidates in hopes of denying either of the two major candidates an electoral college majority. Both attempts (in 1948 and 1968) failed, but not by much - in both cases a shift in the result of two close states would have forced the respective elections into the House.

In modern elections, a running mate is often selected in order to appeal to a different set of voters. A Habitation-Clause issue arose during the 2000 presidential election contested by George W. Bush (alongside running-mate Dick Cheney) and Al Gore (alongside Joe Lieberman), because it was alleged that Bush and Cheney were both inhabitants of Texas, and that the Texas electors therefore violated the Twelfth Amendment in casting their ballots for both. Bush's residency was unquestioned, as he was Governor of Texas at the time. Cheney and his wife had moved to Dallas five years earlier when he assumed the role of chief executive at Halliburton. Cheney grew up in Wyoming and had represented it in Congress. A few months before the election, he switched his voter registration and driver's license to Wyoming and put his home in Dallas up for sale. Three Texas voters challenged the election in a federal court in Dallas and then appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit where it was dismissed.[8]

Proposal and ratification

The Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment on December 9, 1803 and the following states ratified the amendment:[9]

- North Carolina (December 21, 1803)

- Maryland (December 24, 1803)

- Kentucky (December 27, 1803)

- Ohio (December 30, 1803)

- Pennsylvania (January 5, 1804)

- Vermont (January 30, 1804)

- Virginia (February 3, 1804)

- New York (February 10, 1804)

- New Jersey (February 22, 1804)

- Rhode Island (March 12, 1804)

- South Carolina (May 15, 1804)

- Georgia (May 19, 1804)

- New Hampshire (June 15, 1804)

Ratification was completed on June 15, 1804. The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following state:

- Tennessee (July 27, 1804)

In addition, the following states rejected the amendment:

- Delaware (January 18, 1804)

- Massachusetts (February 3, 1804)

- Connecticut (May 10, 1804)

See also

Notes

- ↑ This sentence is superseded by Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment

- ↑ "Constitution of the United States: Amendments 11-27". National Archives. http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/constitution_amendments_11-27.html. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ [1] This prohibition was designed to keep electors from voting for two "favorite sons" of their respective states.

- ↑ See Article II, Section 1, Clause 5

- ↑ The question of how the constitutional eligibility provided by the Twelfth Amendment and the Twenty-second Amendment applies to constitutional eligibility of persons having previously held the office of President, or acted as President, to the office of Vice President, having not been adjudicated by the Supreme Court nor specified by ratification of an additional constitutional amendment, remains constitutionally inexplicit/unclear.

- ↑ The popular vote in 1824 did not consist of all of the states, since many states chose their electors through their legislatures instead of by a vote of their people.

- ↑ "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives". About.com. http://history1800s.about.com/od/leaders/a/electionof1824.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Obscure Texas Case Offers Peek Into Role Of Court Nominee, The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 7, 2005.

- ↑ Mount, Steve (January 2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". http://www.usconstitution.net/constamrat.html. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

External links

- Constitution of the United States, via Wikisource

- Twelfth Amendment, via National Archives

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Twelfth Amendment, via Cornell Law School

- Ellis, E. S. (1903). Thomas Jefferson: A Character Sketch., via Project Gutenberg

- U. S. Electoral College, via Office of the Federal Register

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||